|

|

![]()

|

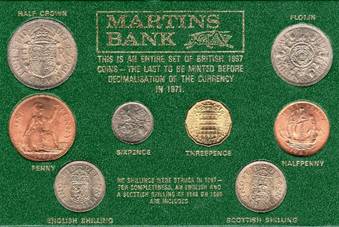

MARTINS

BANK AND DECIMALISATION |

![]()

|

Jumping the gun?

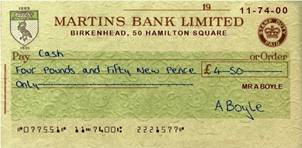

Counting up, counting down… Although Martins Bank sadly does not survive to

oversee the conversion of its accounts to the new decimal currency, it is

still very much at the forefront of the planning and decision making that

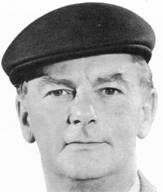

will give us the 100p Pound we still have today. This is because Ron Hindle, Manager of the

Bank’s Organisation Research and Development Department is chair of the

committee charged with sorting the whole thing out. Ron is

already the brain behind Martins’ groundbreaking computer development, and

leaves much of the system we still use for clearing cheques as his

legacy. In 1967, as Chair of the

British Banks Decimalisation Study Group he travels to Australia and New

Zealand to find out how these countries have coped with the adoption of

decimal currency, and, more importantly HOW we in Britain should do the same.

Ron Hindle

(Right) and his fellow Group members pose for the Wellington Evening Post in

July 1967. Image ©

Wellington Evening Post / Martins Bank Archive Collection - Ron Hindle Estate

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

©

1967 Wanganui Herald, Wellington Evening Post, The

West Australian and Ron Hindle Estate |

The Group’s visit down-under attracts a considerable amount of interest

from the press, for once able to bask in the knowledge that they are ahead of

the UK in decimalisation by a number of Years. In Britain, decimalisation has already been

on the cards since the early 1960s.

Following successful decimalisation schemes in other countries,

the British Government sets up the Committee of the

Inquiry on Decimal Currency (Halsbury Committee) in 1961, which

reports in 1963.

There follows much discussion

about how to achieve a decimalisation, including halving the value of the

pound, before the system we know today

is finally adopted. Martins is in the

final throes of takeover by Barclays when in October 1969 the ten shilling

note is replaced by the 50 pence coin.

The British Pound remains intact after

decimalisation, unlike in Australia and New Zealand, where the value is

halved to create the Dollar. Between 1928 and 1957, long before

decimalisation, Martins Bank issues its own £1 notes on the Isle of Man. Altogether nine non-Manx banks are

permitted to issue £1 notes on the island between 1882 and 1961. Tynwald then decides that ALL future Isle

of Man banknotes can only be issued by them. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

x Ten-Bob Notes – still missed today |

x Martins Manx

Pound |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Images © Martins

Bank Archive Collections

After touring New Zealand and

Australia in July 1967, Ron writes the following article in the staff

magazine in which he looks at the merits of having a decimal currency, and

how this has already taken place on the other side of the world. He also speculates on the size and shape of

Britain’s new coins, noting wryly that a coin with edges will surely wreak

havoc in a cloth pocket! Little does

he know how right he will be…

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Whatever savings were anticipated are lost as a result. In New

Zealand a coin of similar value was issued and in the first few days it

seemed to be acceptable. Will this be so a year from now? The reason given in Australia is that the

50c coin is too easily mistaken for a 20c coin or older 2s. piece. Though

different in size, in the metal used and in design, the public does not want

it. New Zealand gave their 50c coin a distinctive feature—the milling round the edge is broken by four smooth segments.

Is this the secret of success ? We need to know, if Britain is to make a

success of a 50 new penny coin (10s. in the present money). How about a

different shape? Imagine the havoc

that a square coin (even with rounded corners) will cause in a cloth pocket. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Australian Decimalisation 1966. The one and two cent coins are

dropped in 1990, being of little more than nuisance value. |

“Tabloid education

is fashionable today - people learn through the medium

of comic strips. There has to be a cartoon character. So 'Dollar Bill' was born” |

||||||||||||||||

|

‘Tender high’ The Australians expounded an interesting theory - that men pick out coins from their pocket largely by the

sense of touch while women take them from their purses mainly by appearance.

The coins of smallest value both in Australia and New Zealand are worth 1

cent and 2 cents. They avoided 4 cents by opting for a major unit equal to

10s. in the old currency. Quite rightly they preferred coins smaller than the

clumsy penny. In New Zealand no secret was made of the fact that the

operation of decimalisation was being covered by savings arising from the

reduced metallic content of the low value coins. But are these coins too small?

In practice the banks find that the variations in weight of coins of

the same value are such that checking values of bags by weight is a much more

risky procedure than it was with pennies - and that is so now,

when all the coins are new! It seems that tolerance in weight is not in

proportion to the stated weights of the coin but it increases proportionately

with larger coins. Tabloid education is fashionable today - people learn through the medium of comic strips. There has to

be a cartoon character. So 'Dollar Bill' was born. There had to be songs and

rhymes too. What about nursery rhymes ? Could 'Sing a song of sixpence'

become 'Sing a song of five cents'? 'Tender high' was the refrain on D.C. (decimal changeover) Day.

What did it mean? An official conversion table had been published and

appeared on the sides of pens and pencils, inside purses and on every gimmick

that could be devised. But it was seemingly only for bankers and such elite. You must tender high - as high as the next multiple of 5 cents (6d.) above what you

want to pay. Then you will get cents in change. Imagine how this went on. A man gets on a bus and asks for a

7-cent ticket. His pencil tells him that this is equivalent to 8d. which he

offers to the driver (one-man buses always). No, says the driver, a shilling

please and I will give you 3 cents change. The newsvendor sells papers

previously 4d. and now priced at 4 cents. But 4 cents equals 5d., the pencil

says. The passer-by offers 4d. - just trying it on,

or maybe forgetting the changeover. No, says the newsvendor. Remembering the

pencil the buyer offers 5d. No, says the newsvendor, I want 6d. so that I can

give you 1 cent change. The argument starts. The paper was only 4d. last week

- and why should I not get it now for 5d. ? The newsvendor gives in and takes

the 5d. - and makes an additional 1 cent!

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

New Zealand old AND new – on the SAME

coin! Interestingly the first New Zealand

decimal $1 coin displays its value in both decimal AND pre-decimal denominations

to demonstrate that one new dollar is equal to ten old shillings. Image © Reserve Bank of New Zealand - http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/ |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Progressive changeover A statistical discovery was that whereas bank notes come and go

in the banking system coins stay put. A branch tends to hold a basic reserve

stock of coins which is rarely touched. This helped in the withdrawal of the

old coins after the changeover. On the changeover day all stocks of the old

coin held by the branches were 'frozen', not to be issued except in case of

emergency, and were withdrawn later without the complication of sorting new

coin from old. If the new coins are to be issued in advance of changeover in

this country, as is now suggested, it will not be possible to carry out such

a clean withdrawal of old currency after conversion. Conversion cannot be done overnight. In Australia, for instance,

the operation of dual currency lasted for 18 months, a progressive

changeover, zone by zone, taking place, largely determined by the question of

machine conversion. During this time shops were advised to work in the

currency that their machinery was made for. Thus the 'tender high' philosophy

had to operate for some time. This was not fully recognised by some New

Zealand bank managers who omitted to keep some £.s.d. currency for issue to those of their customers who were

still dealing in £.s.d. This sort of thing complicates the task of the

cashier. During the dual currency period small items (groceries and the

like) are commonly marked in both currencies. Imagine the fun in this country

if we persist in calling the minor unit a penny (or even a new penny), the

new penny being worth 2.4 old pennies. The actual price tickets should be

clear enough as a different letter will be used for the two pennies ('d' for

old and 'p' for new). In conversation, however, it will not be so easy.

Imagine the grocer saying 'Mrs Smith, sugar is fourpence a pound today'. 'That's

cheap' says Mrs Smith, 'I'll take 10 Ib. before it goes up. Here is 3s. 4d.'

'Oh no, Mrs Smith that comes to 40 pence. If you want to pay in the old

currency it will be 8s.' Imagine, too, the tricks that the unscrupulous

trader might be up to.

Ups and downs Britain, basing its new currency on the £, will be spared the problems that arise at the top end of the

scale due to a change in major unit. The Australian and New Zealand new

dollar is equivalent to 10s. Houses there sound cheaper if still advertised

in £'s. But the best racket arises with motor cars. These are still often

advertised in £'s, but your trade-in is quoted in dollars. 'Yes sir, you can

have this magnificent car for £1,000 and we will give you an allowance of 400

dollars for your old model.' The customers pays up 1,600 dollars and then

realises that his trade-in allowance was only £200!

Banks generally reckon to balance their books but currency conversion beats

them. Perhaps for the first time they have to instruct their branches not to

balance —or at least they have

to tell them what to do with inevitable differences. This arises from the

fact that old pence cannot be converted exactly into new pence; some figures

are rounded up and some are rounded down, and only by an arithmetic freak

will the 'ups' balance the 'downs'. The more the amounts the less will be the

difference, always assuming that the nimble-fingered machinist makes no

mistakes and anyway, by then, every branch will be 'computerised' so maybe

they won't care much. Some shocks may well be coming to managers. Quite likely the

bank's books will be closed to customers for a while to permit cheques in the

pipeline to find their way into the accounts. Then for the first time,

managers will really know how far a customer is overdrawing on his account!

These are the sort of practical things that arise in decimalising the

currency. The basic principle is simple enough, but there will be a multitude

of little situations to deal with and it will not only call for training and

knowledge on the part of the bank staffs who will bear the brunt, but for

quite a bit of tact and understanding.

|

||||||||||||||||||

<