|

Grimsby joins the

smattering of Martins Bank’s Branches in Lincolnshire, in September 1966 –

another full Branch is opened in the same year at Boston and a sub-Branch to

Lincoln is opened at North Hykeham.

Grimsby will however be the last Branch to fly the flag for Martins in

this part of the Country, as the merger with Barclays is just around the

corner and branch closures will be inevitable. Both Lincoln and North Hykeham

close in 1969, Grimsby in 1970 after fewer than four years open, leaving

Boston and Spalding to continue the name of Martins. Boston survives until the end of 1992, and

Spalding even longer, until May 2024. Grimsby joins the

smattering of Martins Bank’s Branches in Lincolnshire, in September 1966 –

another full Branch is opened in the same year at Boston and a sub-Branch to

Lincoln is opened at North Hykeham.

Grimsby will however be the last Branch to fly the flag for Martins in

this part of the Country, as the merger with Barclays is just around the

corner and branch closures will be inevitable. Both Lincoln and North Hykeham

close in 1969, Grimsby in 1970 after fewer than four years open, leaving

Boston and Spalding to continue the name of Martins. Boston survives until the end of 1992, and

Spalding even longer, until May 2024.

|

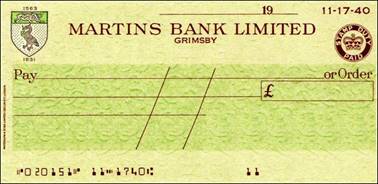

In Service: September 1966 to 8 May 1970

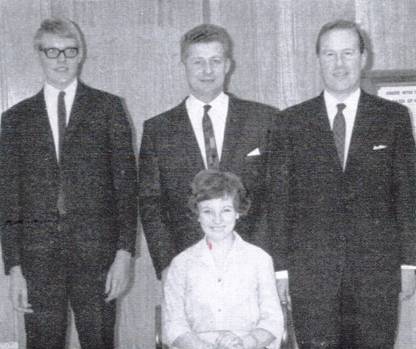

Image © Barclays Ref 0030-1127

|

|

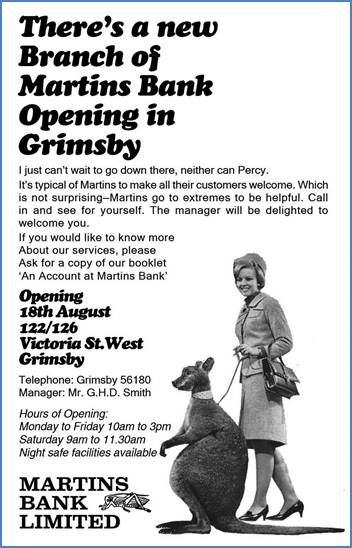

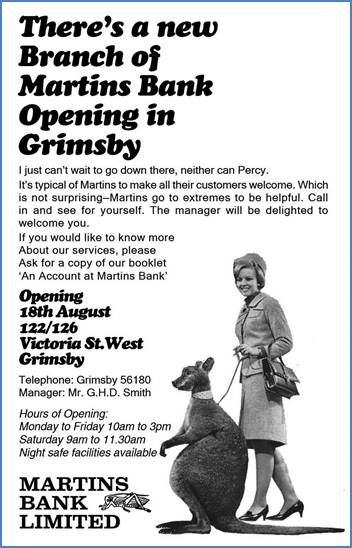

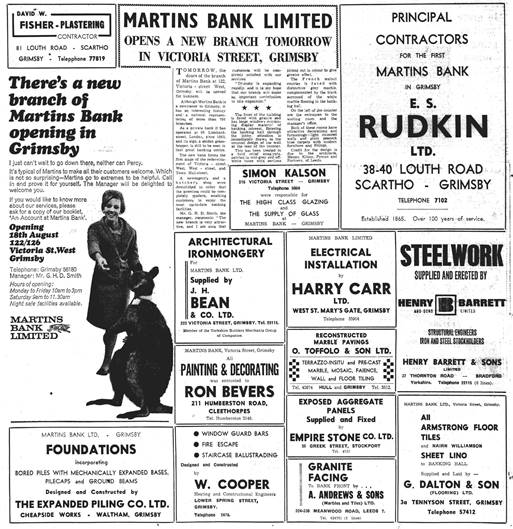

A grand opening in Grimsby!

The Grimsby Evening Telegraph of 17 August 1966 is

all a-buzz with the excitement of a new bank about to makes it’s mark on the

town! We are in the middle of one of

the Bank’s most loved advertising campaigns, where zoo animals accompany

human to the bank as if it were commonplace.

For Grimsby, it is the turn of Percy the Wallaby, who apparently “can’t

wait” to escort his young lady friend to the opening of yet another new

branch of Martins Bank. The newspaper spread is a well-worn way of gaining

advertising for the bank, and those contractors and other agents responsible

for the design and execution of this new branch…

|

Image © Martins Bank Archive Collections

|

Image © Reach PLC and Find my Past created

courtesy of THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD.

Reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive

|

|

Halfway up on the

right-hand side…

As Grimsby

Branch is destined to bow out so early, it is perhaps just as well that not

long after the office is opened for business, Martins Bank Magazine

provides a very lengthy and detailed article about the town, the Branch,

and the Staff, and starts by getting to grips with just what,

exactly, Grimsby is for…

|

|

remembering

where Grimsby

is – halfway up on the

right-hand side, for those who do not know - one might reasonably wonder

why the Bank opened a branch there. The nearest sizeable towns are Scunthorpe, a music-hall joke

town booming precariously on steel 30 miles to the west, and Lincoln 36

miles to the south-west. Between these two communities and Grimsby lie the

Lincolnshire Wolds and acres of rich farmland. The signposts guiding one

from the west fail to acknowledge Grimsby's existence until one is 20 miles

from it and even then, its name is linked with the adjoining borough of

Cleethorpes, another music-hall joke town sometimes called

Sheffield-by-the-Sea. These depressing thoughts may have been prompted by a 160-mile

drive in a continuous downpour, but we told ourselves that none of the

great explorers would ever have discovered anything had they turned back

when conditions were unfavourable. The rain eased as we approached Grimsby

which surprised us by its enormity: it has a population of 90,000 and its

adjoining resort and dormitory has 40,000. The second surprise was the

realisation that it is attractive and clean, with many open spaces, modern

buildings, and schools. We began to feel better and when the sun emerged

for half an hour, we actually wondered why we had not come to Grimsby

before. One reason is that to us and to many others Grimsby and fish are

synonymous, the other is that when the east winds blow off the North Sea

across the Humber mouth even brass monkeys would head for warmer climes.

But in September, apart from a diesel locomotive which yahoo-ed outside the

hotel window at intervals throughout the night, Grimsby was most

hospitable.

|

Image

© Martins Bank Archive Collections

|

It is a bustling

place, but one has to dig beneath the surface to realise how much it is

dependent on the sea and has been since the Danes settled there a

thousand years ago: only when the original haven silted up in the 16th

century did its inhabitants turn to the land for a living. Its survival

provides a remarkable story of religious, political, legal, and economic

skulduggery: laws were made to be broken, those who administered them

were too often on the make, and loyalties were bought and sacrificed.

In 1524 the mayor of

the town received a peremptory demand from 'a gentleman' to deal

leniently with a miscreant 'or else ye shall cause me to put the matter

to further knowledge, which I should be sorry to do, as knoweth our

Lord'.

|

|

|

Forty years later 21

absentees from church, charged with non-attendance, were found to have gone

wildfowling: within a few years the vicar was charged with playing bowls

and football— sports apparently more vicious in those days than bull-and

bearbaiting.

Through all this runs a history of battles with the elements and of

primitive ships trading with far places. It was another gentleman—a railway director—who

raised Grimsby out of the mud and conflict when he persuaded his board to

build a railway, completed in 1848, and to build a dock. By 1851 the

population had doubled to nearly 9,000. Today Grimsby is acknowledged as the

premier fishing port of the world, with the biggest cold storage capacity

in the United Kingdom. Quite apart from a prodigious trade through the

Royal Dock, notably in timber and bacon, the development of the 63-acre

Fish Dock has to be seen before one can appreciate the progress since

orphan 'apprentices' were sent as crew on the earliest steam trawlers. A

modern trawler with freezing equipment costs £500,000 so, not

surprisingly, the owners of today are limited companies, but skippers and

crews are handsomely rewarded for what is still a tough and sometimes

hazardous life.

|

|

Image

© Martins Bank Archive Collections

|

Everything from repairs

and the fitting and victualling of the ships to the landing, marketing,

packing, storing and transport of their catch is handled at Grimsby, and

the wealth of the industry is reflected in the shops and the homes. Though

the town lives primarily off, if not on, fish there is no smell in these

days of quick freezing except on the 'pontoon', the long-covered sheds, and

offices where morning sales are conducted through 350 individual firms of

fish merchants.

The town has other

concerns—rubber, chemical and oil interests have been established

along the Humber bank—and this, one might say, is where we came in and why

the Bank came into Grimsby, for Humberside in the future is going to be

quite something. On the north bank is Hull 'at the end of the road to

nowhere' as we wrote some time ago, and to the south are Immingham and

Grimsby with ample room for expansion as far inland as Scunthorpe if necessary. Humberside is something to watch and, with a return

to economic sanity, the question 'why did we open at Grimsby?' could soon

become 'where do we open next?'

|

|

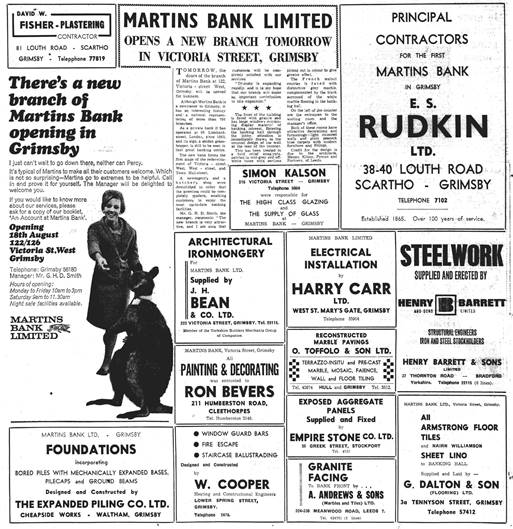

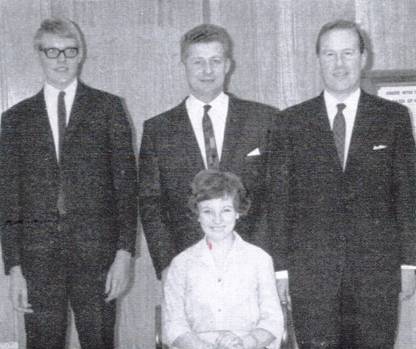

The new branch is all one would expect it to be, strikingly

modern in a part of the town undergoing redevelopment, the outstanding

features being the grey marble counter face and the rear wall of the

banking hall in bold relief Anaglypta. Mr

G. H. D. Smith's recently acquired knowledge of Grimsby's main industry

following his two years as manager in agricultural Selby qualify him as the

ideal 'Manager of Ag. and Fish'. Mr R. Taylor is a native of Doncaster

whose recent Inspection experience and Domestic Training Course make him

an able lieutenant. Mrs B. L. Taylor, recently married to a local

schoolteacher, was previously at York Branch for three years and Mr J.

Driver, who was in the recruitment pipeline at the time of our visit, has

since joined the staff.

|

|

The new office goes one better than Grimsby in having a

display window which, by featuring some large reproductions of our

advertisements, was stopping and trapping passers-by. Grimsby itself seems

content to leave the publicity to neighbouring Cleethorpes, relying on

fringe benefits and on its own industry which, it perhaps feels, is

sufficiently well-known. This seems a pity, for even though we may not eat

fish or take cod liver oil we probably use Grimsby fish in some form for

our gardens, pets, or poultry. At least by going there we now know more

about it and what it does. We could even explain it to the small child who

gazed wonderingly at the television and murmured 'I never knew fish had

fingers'.

|

Image © Martins Bank Archive Collections: Stephen Walker

|

|

|

|

|

|

|