|

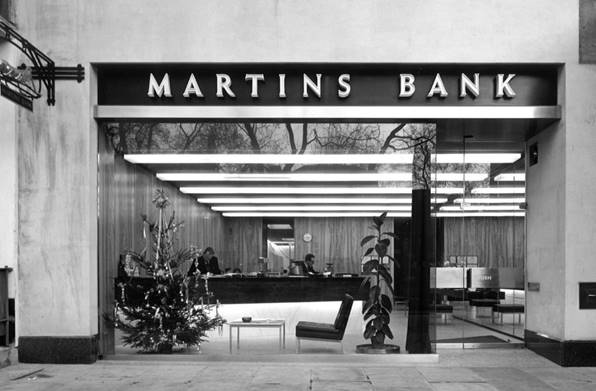

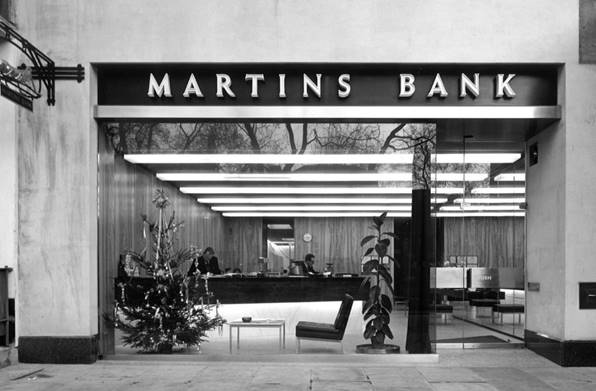

Perhaps it would be churlish to

complain, sometimes the old simply has to make way for the new, and if there is

a plus side, perhaps it is that on the inside at least, Martins Bank’s new

Branch at No 6 Hanover Square does promise the brightest and most spacious

surroundings in which to transact business.

If the idea is to attract young professionals and what are referred to

as “modern marrieds” to open bank accounts and deposit their salaries, this

design might just do it… It does, however seem to be that little bit

futuristic for 1964, a kind of warning shot across the bows that all in the

world of architecture is not at peace with itself. Yet in Post-War britain, where slums were

still being cleared nearly two decades after the end of hostilities, such a

vision of concrete, glass and metal must have seemed so appealing to almost

everyone tired of dark wood and forbidding stone. Some might have foreseen

today’s backlash against all that is square, rectangular, box-like, dead

behind the eyes and so on, but at the time, Architects were the new gods,

first drawing, then building tomorrow as if it was a kind of conjuring trick.

The Bank’s building at 5

Hanover Square, although attractive, was extremely sick and in dire need of

attention, but just what were the events that made moving to premises

situated only next door so fraught with diffulty and danger? Read on, as this article from Martins Bank

Magazine’s Winter 1964 Edition shows us all how to achieve:

|

In Service: 1964 until 4 April 1977

Branch Images © Barclays Ref 0033-0256

|

|

Some

lively steps in the Hanover Square Dance…

in

recent years there has been a noticeable increase in the number of Head

Office circulars advising new addresses for existing branches and, whether

the changes are due to progress, expansion, modernisation, or town-planning,

the transfer from the old office to the new, apart from petty annoyances, is

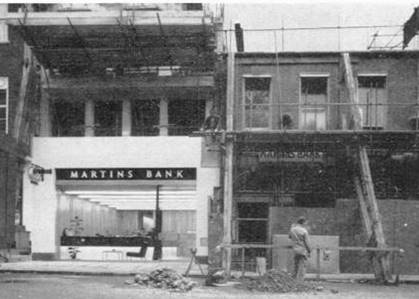

usually effected without undue trouble. A

move to new premises next door would, naturally, seem the easiest to

accomplish for one merely has to continue until the new premises are ready

when, in a week-end, cash, cabinets, securities—well, many of us have been through it and there is no point

dwelling on it. Hanover Square branch in London should have provided just

such a simple example, for Number 5 (the old office) is next door to Number 6

(the new). Perhaps you remember altering the number in the branch address

book in October? But did you know that some six months earlier No 5 made a

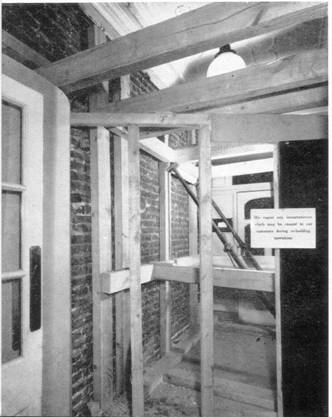

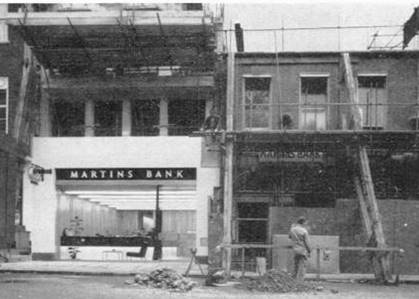

determined attempt at moving into No 6? No? Well this is the story. Early this year No 6 had, as the

photograph shows, become a hole in the ground with the flank of No 5

supported by a network of steel tubing. The staff at No 5 were, however,

becoming suspicious that cracks appearing in the plaster were tending to

widen and so 'tell-tale' strips had been stuck across these to see if this

really was so. in

recent years there has been a noticeable increase in the number of Head

Office circulars advising new addresses for existing branches and, whether

the changes are due to progress, expansion, modernisation, or town-planning,

the transfer from the old office to the new, apart from petty annoyances, is

usually effected without undue trouble. A

move to new premises next door would, naturally, seem the easiest to

accomplish for one merely has to continue until the new premises are ready

when, in a week-end, cash, cabinets, securities—well, many of us have been through it and there is no point

dwelling on it. Hanover Square branch in London should have provided just

such a simple example, for Number 5 (the old office) is next door to Number 6

(the new). Perhaps you remember altering the number in the branch address

book in October? But did you know that some six months earlier No 5 made a

determined attempt at moving into No 6? No? Well this is the story. Early this year No 6 had, as the

photograph shows, become a hole in the ground with the flank of No 5

supported by a network of steel tubing. The staff at No 5 were, however,

becoming suspicious that cracks appearing in the plaster were tending to

widen and so 'tell-tale' strips had been stuck across these to see if this

really was so.

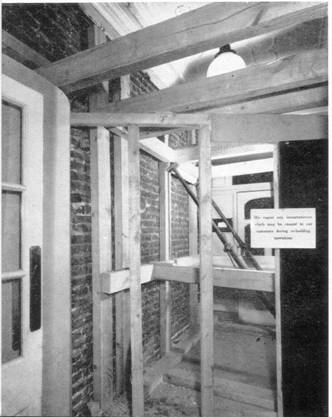

One morning some mortar fell precariously near Mr E. G. Vodden,

the branch messenger, as he entered the front door. Looking up he saw large

cracks in the front wall which appeared to be bulging more than might be

expected even of a building about 200 years old. Later in the morning a

member of the staff was fascinated to see a fresh crack appear in the office

wall and creep steadily upwards before his eyes. Premises Department were

notified, the architect appeared, took one look and gave the order to evacuate. A suggestion that the office should remain

open until 3 o'clock met with the response 'Never mind 3 o'clock—I mean now!', and he would not be responsible for the safety of

anybody who elected to stay. It was 1.15 p.m. A phone call to District Office enabled

the qualifications to speak in unqualified terms and gain Authority's

immediate response. Fortunately Oxford Circus branch is less than 5 minutes'

walk away and everybody there edged up to make room for the Hanover Square

staff whose Manager, Mr John Wilson, seized and took to lunch the customer

who had waited and watched with such tolerance and fascination as the drama

unfolded. One morning some mortar fell precariously near Mr E. G. Vodden,

the branch messenger, as he entered the front door. Looking up he saw large

cracks in the front wall which appeared to be bulging more than might be

expected even of a building about 200 years old. Later in the morning a

member of the staff was fascinated to see a fresh crack appear in the office

wall and creep steadily upwards before his eyes. Premises Department were

notified, the architect appeared, took one look and gave the order to evacuate. A suggestion that the office should remain

open until 3 o'clock met with the response 'Never mind 3 o'clock—I mean now!', and he would not be responsible for the safety of

anybody who elected to stay. It was 1.15 p.m. A phone call to District Office enabled

the qualifications to speak in unqualified terms and gain Authority's

immediate response. Fortunately Oxford Circus branch is less than 5 minutes'

walk away and everybody there edged up to make room for the Hanover Square

staff whose Manager, Mr John Wilson, seized and took to lunch the customer

who had waited and watched with such tolerance and fascination as the drama

unfolded.

Senior colleagues and staff-acted with such speed and efficiency

that on Mr Wilson's return he found on the

front door a most unusual notice requiring callers to go to Oxford

Circus branch where temporary counter service was Available. Also outside were a group of workmen who

announced with unconcealed delight 'They've gone. Guv!' The afternoon

was spent in discussions with the Bank's Surveyors, District Surveyors, Site

Foremen and representatives from Premises Department. All-night work was arranged so that the

branch could re-open in the morning. Mercifully the Inspectors did not show

up for a cash count for they would have discovered everything bundled away,

unbalanced. The staff worked with

great good humour in their temporary quarters and the customers reacted

splendidly, even the one who was told he couldn't have his box from the

strongroom that day! Following a mass inspection by building

experts next morning through the entire six floors of No5, it was decided

that the now heavily buttressed branch could

safely be re-opened and at 10 o'clock the assembled staff were detailed to

return to Oxford Circus and bring back the vouchers, ledgers, etc. As the

front door opened, a customer, waiting patiently to enter, was astounded to

see some fifteen members of the staff troop out in procession and imagined he

was witnessing an unheard-of phenomenon—a walk-out of bank staff. That might have been the end

of the story but, as the new premises grew alongside, the upper floors of the

old building, which were not part of our office, were demolished. Senior colleagues and staff-acted with such speed and efficiency

that on Mr Wilson's return he found on the

front door a most unusual notice requiring callers to go to Oxford

Circus branch where temporary counter service was Available. Also outside were a group of workmen who

announced with unconcealed delight 'They've gone. Guv!' The afternoon

was spent in discussions with the Bank's Surveyors, District Surveyors, Site

Foremen and representatives from Premises Department. All-night work was arranged so that the

branch could re-open in the morning. Mercifully the Inspectors did not show

up for a cash count for they would have discovered everything bundled away,

unbalanced. The staff worked with

great good humour in their temporary quarters and the customers reacted

splendidly, even the one who was told he couldn't have his box from the

strongroom that day! Following a mass inspection by building

experts next morning through the entire six floors of No5, it was decided

that the now heavily buttressed branch could

safely be re-opened and at 10 o'clock the assembled staff were detailed to

return to Oxford Circus and bring back the vouchers, ledgers, etc. As the

front door opened, a customer, waiting patiently to enter, was astounded to

see some fifteen members of the staff troop out in procession and imagined he

was witnessing an unheard-of phenomenon—a walk-out of bank staff. That might have been the end

of the story but, as the new premises grew alongside, the upper floors of the

old building, which were not part of our office, were demolished.

They included a chimney

stack. When the typists entered their first-floor  room one morning they encountered a

choking, gritty smog. Nobody outside had thought to advise those inside to

seal off the fireplace. We heard of

this when we called at No 5 in October, to meet Mr Wilson and his staff. He opened the curtains across the window in

his room to reveal long panes of glass which looked as if nasty little boys

had been slopping nasty things about—the result of a spilt

barrow-load of cement cascading into the narrow well between the buildings. We went with him

all over that fated, impatient building and saw for ourselves the cracked

panes where careless scaffolding poles and other secret weapons had forced

entry for the rain. We saw the ceilings on the first floor with their

stained, cracked and peeling plaster, and one section with no plaster at all.

For a temporary roof surface had to be laid when the floors above were

removed but, of course, the weather beat the workmen to it. Also, about that

time, a gully in the well became choked with rubble so that, in a prolonged

downpour, the water level rose higher and higher until it eventually found a

crack and poured into the basement just at the start of a day. A

hurriedly-mustered squad from the adjoining site spent the morning sweeping

water resolutely towards a toilet drain in an adjoining room and kept it away

from the strongroom. Then in the basement we saw four 7-foot-high built-in,

wooden stationery cupboards. A hosepipe left running one week-end on the

site next door caused a healthy

build-up of water in these cupboards, the full extent of which was only

discovered on the opening of a door. room one morning they encountered a

choking, gritty smog. Nobody outside had thought to advise those inside to

seal off the fireplace. We heard of

this when we called at No 5 in October, to meet Mr Wilson and his staff. He opened the curtains across the window in

his room to reveal long panes of glass which looked as if nasty little boys

had been slopping nasty things about—the result of a spilt

barrow-load of cement cascading into the narrow well between the buildings. We went with him

all over that fated, impatient building and saw for ourselves the cracked

panes where careless scaffolding poles and other secret weapons had forced

entry for the rain. We saw the ceilings on the first floor with their

stained, cracked and peeling plaster, and one section with no plaster at all.

For a temporary roof surface had to be laid when the floors above were

removed but, of course, the weather beat the workmen to it. Also, about that

time, a gully in the well became choked with rubble so that, in a prolonged

downpour, the water level rose higher and higher until it eventually found a

crack and poured into the basement just at the start of a day. A

hurriedly-mustered squad from the adjoining site spent the morning sweeping

water resolutely towards a toilet drain in an adjoining room and kept it away

from the strongroom. Then in the basement we saw four 7-foot-high built-in,

wooden stationery cupboards. A hosepipe left running one week-end on the

site next door caused a healthy

build-up of water in these cupboards, the full extent of which was only

discovered on the opening of a door.

|

|

Is it surprising

that No 5 is suspected of having developed almost human frailties; that it is

fed up and wants the people out so that it can be rebuilt and take its place

among London's modem buildings? In the first-floor machine room, overlooking

the square itself, many of the staff must have wished for a chance to work

temporarily in a marquee out there under the trees rather than in that

crowded room with its ominous cracks extending from floor level and

disappearing, at a height of three feet and with heaven knows what diabolical intent, behind the acoustic

tiles reaching to the lofty ceiling. But even on the ground floor, a crack up

the wall at the back of a pillar, into which we fitted a notebook without

touching anything solid, was pointed out to us as a matter of passing

interest. Talking to the staff it was impossible to tell who had

been there throughout and who had arrived since the trouble started. There

were plenty of laughs but no symptoms, no nervous twitches. A sense of humour

is a wonderful antidote. And there is a touch of irony in all this for much

of the business at Hanover Square branch concerns Property!

|

|

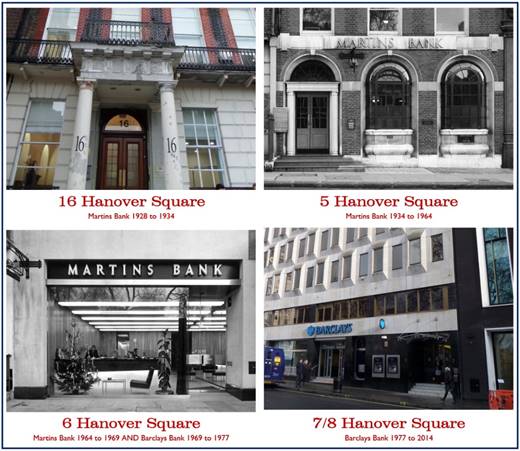

Let’s

take a trip ROUND the SQUARE! Let’s

take a trip ROUND the SQUARE!

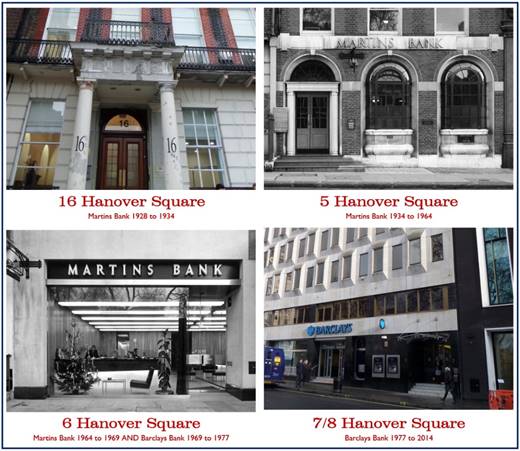

We

are used to some of Martins Bank’s branches having more than one location in

a particular town or City. The story

above of the “Hanover Square Dance” is a little more unusual, as the branch

is accommodated at various points in time by FOUR different addresses within

a stone’s throw of each other.

Martins

Bank inhabits the first three of the four offices, and following yet more

more redevelopment of the area in the 1970s, what was first No 5, then No 6

Hanover Square, soon becomes No 7 AND No 8 – an almost perfect beat

counting for a square dance!

By

the left, quick march: The original Martins Branch at Number 16 is too small

for purpose. After thirty years of operation, number 5 has to be abandoned

for the safety of the newly constructed Number 6. Under Barclays, the

business once more outgrows the building, and expansion into Numbers 7 and 8

is therefore necessary… Our thanks to

Dave Baldwin for the contemporary photographs of Number 16, and Number 7/8

Hanover Square.

|