|

|

![]()

|

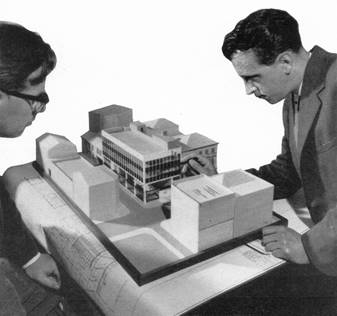

DESIGNING MARTINS BANK |

![]()

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

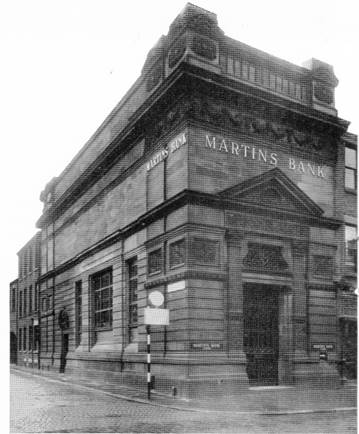

Dark and forbidding -

the interior of the original building. Images © Martins Bank Archive

Collections |

|

There have been cases where work on adjacent sites has had

adverse effects on the Bank’s own work, such as basement flooding. While

weather can often interfere with the work, the progress of a contract is

always to some extent controlled by the ability of specialists to meet the

agreed delivery dates. Some items require a considerable time from order to

delivery in site, and when one remembers that very often the necessary

dimensions are not available until the main structure is in position, it is

easy to see that sometimes delays are very difficult to prevent.

![]()

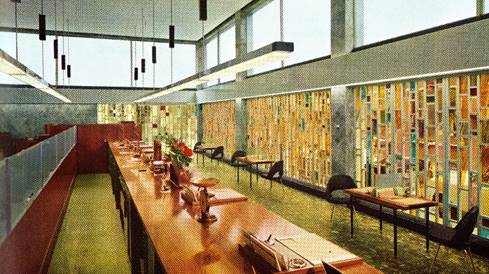

Bright and welcoming, the interior of the new

branch

Image - Martins Bank

Archive Collections

![]()

The story is not yet complete, for there will inevitably be

teething troubles – a door or a drawer which will not close properly; a

heating system which suddenly develops a jinx and tries to roast everybody,

but these matters can be rectified quickly. Customers give their own critical

analysis, usually of the design, and the staff, thankful to be free from dust

and grit, add their opinions – a wall paper is changed. but that is another

story.

![]()

|

|

|

|

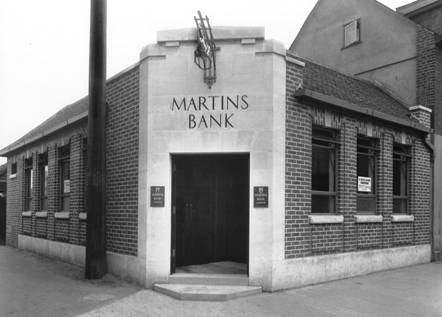

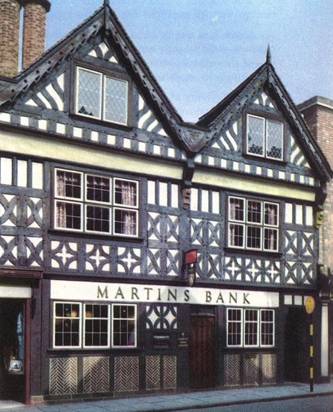

Tyne Dock – Before and After, Images – ©

Martins Bank Archive Collections |

|

A

sympathetic replacement?

![]()

For the staff in particular,

a complete change from an elderly branch building to something new and state

of the art, with much better working conditions is as good as a feast. Martins prides itself on the use of new

innovations, such as central heating through ceiling coils, and special light

fittings that minimise and soften the glare of the modern flouescent bulbs.

The new branches have better staff rest room facilities, many with kitchen

facilities. Between 1963 and 1965, a complete transformation takes place in

Preston, where the former Head Office of the Preston Union Bank is tired,

cramped, dark and miserable. Despite

oozing traditional feelings of security and permanence, the building belongs

to another age, and the two year programme of works that follows sees a large

number of staff relocated to temporary premises, whilst their new and

gleaming statement of sixties hope and glory takes place. Having worked at the “new” Fishergate branch,

our editor is broadly a fan – compared to some of the horror stories you will

encounter on our special feature page, Preston has an elegance of its own,

and a practicality that has kept it in use as a bank for the best part of

fifty years (although the huge reductions in manpower since the 1960s will

have left many an empty floor. Here is

the transformation at Preston, followed by a short extract from Martins Bank

Magazine’s visit to the new Branch in 1965, which provides us with some

architectural details…

For the staff in particular,

a complete change from an elderly branch building to something new and state

of the art, with much better working conditions is as good as a feast. Martins prides itself on the use of new

innovations, such as central heating through ceiling coils, and special light

fittings that minimise and soften the glare of the modern flouescent bulbs.

The new branches have better staff rest room facilities, many with kitchen

facilities. Between 1963 and 1965, a complete transformation takes place in

Preston, where the former Head Office of the Preston Union Bank is tired,

cramped, dark and miserable. Despite

oozing traditional feelings of security and permanence, the building belongs

to another age, and the two year programme of works that follows sees a large

number of staff relocated to temporary premises, whilst their new and

gleaming statement of sixties hope and glory takes place. Having worked at the “new” Fishergate branch,

our editor is broadly a fan – compared to some of the horror stories you will

encounter on our special feature page, Preston has an elegance of its own,

and a practicality that has kept it in use as a bank for the best part of

fifty years (although the huge reductions in manpower since the 1960s will

have left many an empty floor. Here is

the transformation at Preston, followed by a short extract from Martins Bank

Magazine’s visit to the new Branch in 1965, which provides us with some

architectural details…

![]()

|

|

|

|

With a nod to the past – the two branches occupy

broadly the same amount of space… Images – Martins Bank Archive

(Left) and © Barclays (Right) |

|

“The

entrance porch is of clear glass but the windows are of hand-made tinted

glass set in aluminium frames, the counter is of teak, faced with Sicilian marble, and

the walls of the main banking office are of wide elm boarding with one large

panel of silver-grey marble. The management rooms are lined with cedar of

Lebanon against a maple background and hot water coils in the ceilings warm

all the office areas. The staff kitchen has built-in teak wall cupboards with magnetised catches”…

“The

entrance porch is of clear glass but the windows are of hand-made tinted

glass set in aluminium frames, the counter is of teak, faced with Sicilian marble, and

the walls of the main banking office are of wide elm boarding with one large

panel of silver-grey marble. The management rooms are lined with cedar of

Lebanon against a maple background and hot water coils in the ceilings warm

all the office areas. The staff kitchen has built-in teak wall cupboards with magnetised catches”…

![]()

|

|

|

|

On the inside – from seriously drab to a warm Kodachrome® glow! Images © Martins Bank Archive Collections |

|

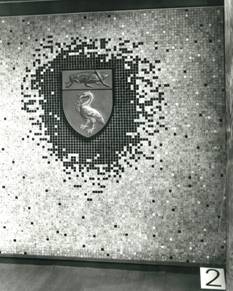

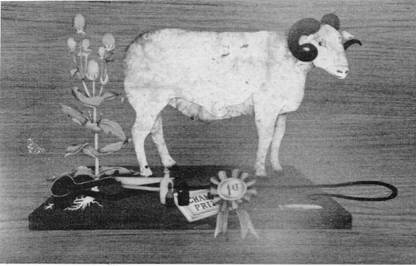

Until 1964, Martins Branches

displayed a number of different representations of the Bank’s name and/or

Coat of Arms on the outside walls of their buildings. From the mid 1950s onwards, a new metal

version of the Grasshopper and the Liver Bird has begun to be seen, but 1964

sees the move into fibreglass, the lightest substance yet used for

this type of signage. Curious to know

just how the mass-production of Bank signs is achieved, Martins Bank Magazine

lifts the lid on the process in its Summer 1964 issue…

Fibreglass – the way

forward…

![]()

|

|

|

![]()

since the last war, through research and experiment, the uses of fibreglass

have developed to such an extent that there are now companies engaged solely

in the manufacture of fibreglass products. Such a company is Carleton Russell Limited whose

works at Loughborough we visited recently. The company makes fibreglass

signs and displays and has produced several of our Bank signs. At the time of

our visit the finishing touches were being made to the huge sign, seen in the colour

photograph above, which now gleams upon customers entering our branch at Digbeth,

Birmingham. Why fibreglass?

Two of its advantages, lightness and flexibility, have much to recommend it

as the material for a wall sign, either inside or outside a building. The

Coats of Arms carved in stone which once surmounted the two entrances to our

Leeds office have now given way to

fibre-glass reproductions.

Weather resistance is another valuable property of these signs and Hove

branch, for example, exposed to coastal weather, is saved frequent cleaning

and retouching costs by having its external sign made from fibreglass.

since the last war, through research and experiment, the uses of fibreglass

have developed to such an extent that there are now companies engaged solely

in the manufacture of fibreglass products. Such a company is Carleton Russell Limited whose

works at Loughborough we visited recently. The company makes fibreglass

signs and displays and has produced several of our Bank signs. At the time of

our visit the finishing touches were being made to the huge sign, seen in the colour

photograph above, which now gleams upon customers entering our branch at Digbeth,

Birmingham. Why fibreglass?

Two of its advantages, lightness and flexibility, have much to recommend it

as the material for a wall sign, either inside or outside a building. The

Coats of Arms carved in stone which once surmounted the two entrances to our

Leeds office have now given way to

fibre-glass reproductions.

Weather resistance is another valuable property of these signs and Hove

branch, for example, exposed to coastal weather, is saved frequent cleaning

and retouching costs by having its external sign made from fibreglass.

![]()

As the name suggests, glass

fibre is one of the basic

materials used in producing

fibreglass. The other is a polyester

resin, a plastic substance which bonds the glass fibre

into a strong but resilient laminate. To follow the stages of producing a sign from start to

finish, our tour of the works began at the modeller's

room. Here a model is prepared from the design, which may be merely a

blown-up photograph, the modeller working with clay which is kept damp to prevent hardening. In

this way, once the mould has been made from the model, the clay can be used

again.

As the name suggests, glass

fibre is one of the basic

materials used in producing

fibreglass. The other is a polyester

resin, a plastic substance which bonds the glass fibre

into a strong but resilient laminate. To follow the stages of producing a sign from start to

finish, our tour of the works began at the modeller's

room. Here a model is prepared from the design, which may be merely a

blown-up photograph, the modeller working with clay which is kept damp to prevent hardening. In

this way, once the mould has been made from the model, the clay can be used

again.

The material for the mould

is usually liquid rubber which is poured over the model but if many

reproductions are to be made from the same mould, a more robust material—plaster, wood or even fibreglass itself—is used. Once the mould has hardened it is filled

with the polyester resin to provide a 'gel coat' or smooth, outer coating.

This sets in about 30 minutes when another coat of resin is applied and the

glass fibre, in narrow, woven strips like bandages, is pressed into it.

After hardening, the reproduction is taken from the mould and examined for

flaws which can be rectified by careful application of resin.

When all imperfections have

been eliminated the reproduction is left in a curing room for between 24 and

30 hours at a temperature of 140-150 degrees Fahrenheit, this curing process

being essential for the complete binding of the glass fibre and

resin. For a hard, lasting finish the sign is then sprayed with acrylic

paints and finished by hand. We could test for ourselves the lightness and

flexibility of the finished product and we were told of its weather

resistance, but just how strong

fibreglass is we were anxious to

discover. We took a piece of smooth

fibreglass measuring about eight

inches by six inches and no more than ⅛”

thick and tried to snap it.

Our efforts succeeded only

in flexing it slightly. We then watched the same piece struck forcibly by a

golf club which produced a slight dent—on one side only! That could be put right, we were told, by

'filling-in' with fibreglass. It

is scarcely surprising that a material with such advantages—produced at highly

competitive prices too—is continually finding new markets and we left Loughborough wondering where fibreglass might be popping up next.

One thing seems certain: it will not replace steel in the strong room grill.

![]()

Not always

a shock…

![]()

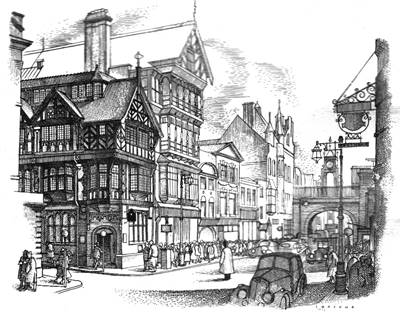

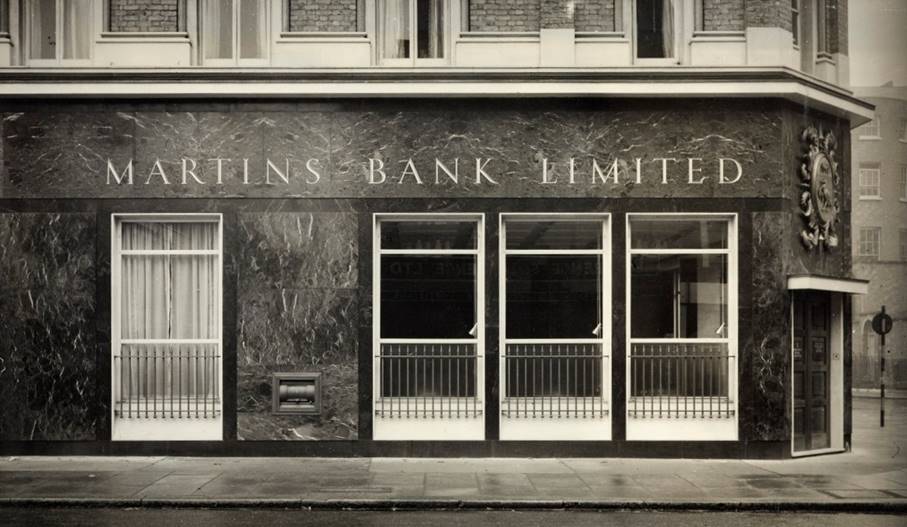

One modernisation that has stood

the test of time as being a beautiful addition to to the Liverpool skyline ,

is of course the Bank’s Head Office at 4 Water Street. Designed on classical

lines, reflecting in sumptuous detail the long association of Liverpool with

all things maritime, the building is about to make another splash here in the

twenty-first century by becoming a luxury hotel that will rival the opulence

and grandeur of many of the top hotels across the World. 4 Water Street, externally grand and

traditional is very much a statement of the future, incorporating internal

features that are way ahead of their time – a clever heating system, the best

electrical and telephone systems that the early 1930s can offer – and many of

these last much longer than originally intended. Our first comparison - of No 7 Water Street

with its successor – is not a “shock

of the new” – it is simply a big step forward in terms of grandeur and

design:

One modernisation that has stood

the test of time as being a beautiful addition to to the Liverpool skyline ,

is of course the Bank’s Head Office at 4 Water Street. Designed on classical

lines, reflecting in sumptuous detail the long association of Liverpool with

all things maritime, the building is about to make another splash here in the

twenty-first century by becoming a luxury hotel that will rival the opulence

and grandeur of many of the top hotels across the World. 4 Water Street, externally grand and

traditional is very much a statement of the future, incorporating internal

features that are way ahead of their time – a clever heating system, the best

electrical and telephone systems that the early 1930s can offer – and many of

these last much longer than originally intended. Our first comparison - of No 7 Water Street

with its successor – is not a “shock

of the new” – it is simply a big step forward in terms of grandeur and

design:

![]()

|

No 7 - Compact and fewer floors |

No 4 – Rising above its rivals |

|

Image © Martins Bank Archive Collections |

|

An artistic march to the

South…

![]()

![]()

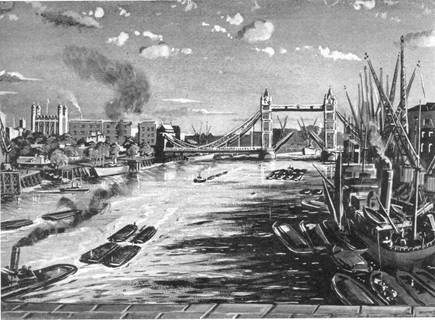

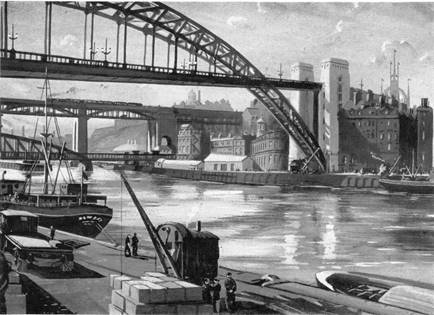

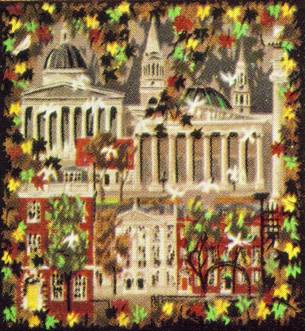

By the mid 1930s, Martins has

begun its thirty year long push to become a truly national bank, and the

South and South-West of England become first outposts, and then

mini-strongholds, with clutches of branches in towns such as Southampton and

Bristol. A decision is taken that the Bank should very much represent the

town or city that its branches inhabit; it begins with the commissioning of

drawings and paintings to be used in advertising, and culminates by the late

1960s in individual and ever more lavish three-dimensional artworks

being made and put into branches. This

is covered in more detail elsewhere within this feature, but here is a

selection of images that show the progression of Martins’ love affair with

artworks…

By the mid 1930s, Martins has

begun its thirty year long push to become a truly national bank, and the

South and South-West of England become first outposts, and then

mini-strongholds, with clutches of branches in towns such as Southampton and

Bristol. A decision is taken that the Bank should very much represent the

town or city that its branches inhabit; it begins with the commissioning of

drawings and paintings to be used in advertising, and culminates by the late

1960s in individual and ever more lavish three-dimensional artworks

being made and put into branches. This

is covered in more detail elsewhere within this feature, but here is a

selection of images that show the progression of Martins’ love affair with

artworks…

![]()

|

|

|

|

The River Avon |

The River Thames |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The River Tyne |

Southampton Water |

|

Images © 1946 Graham Smith |

|

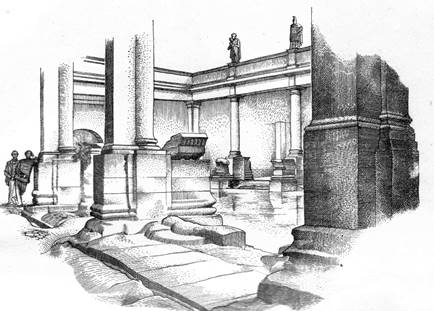

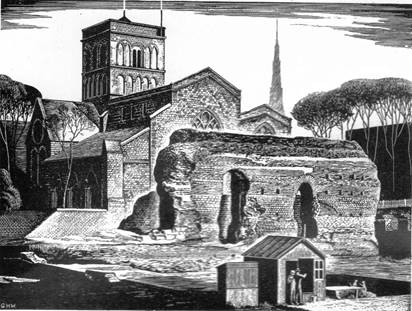

The artist Graham Smith is

commissioned in the 1940s to paint a series of pictures to be used in

advertising under the title of “Famous Banks” – the humour of this idea is in

the name of course, as instead of looking at an image of the Bank of England

for example, you have “the banks” of the River Thames. Around the same time, Geoffrey Wedgwood is

asked to produce a drawing that will represent each of twelve english towns

and cities that had been occupied by the Romans. Advertisements carried the pictures, a

small piece about the Roman occupation of a particular town, and details of

the local Branch of Martins Bank…

The artist Graham Smith is

commissioned in the 1940s to paint a series of pictures to be used in

advertising under the title of “Famous Banks” – the humour of this idea is in

the name of course, as instead of looking at an image of the Bank of England

for example, you have “the banks” of the River Thames. Around the same time, Geoffrey Wedgwood is

asked to produce a drawing that will represent each of twelve english towns

and cities that had been occupied by the Romans. Advertisements carried the pictures, a

small piece about the Roman occupation of a particular town, and details of

the local Branch of Martins Bank…

![]()

|

|

|

|

Bath |

Leicester |

|

|

|

|

Worcester |

Chester |

|

Images © 1947 Geoffrey Wedgwood |

|

The

Roman Towns images and advertisements are a clever way of making up for the

fact that many of the towns and cities involved do not have their own long established Branches of Martins bank – in some cases the paint is

still drying!

The

Roman Towns images and advertisements are a clever way of making up for the

fact that many of the towns and cities involved do not have their own long established Branches of Martins bank – in some cases the paint is

still drying!

As the 1960s approach, Martins starts to think

bigger. The shock of the new is

already on its way, thanks to

architects such as Ernö Goldfinger of the “Brutalism” school of design

– dystopian high rise blocks that solve the housing shortage, but remove the

soul both from an area and its inhabitants.

In the late 1950s,

Martins begins to commission works of art that can take pride of place

in new branches, and in most cases reflect something of the local area – a

kind of “giving back to the people”.

To begin with, this is neither a grand nor hollow gesture, and the

character of many a branch is decided by its own unique internal décor and

its artwork. Our next gallery combines

sixties interior design, with some one off pieces lovingly made to be proudly

exhibited within them…

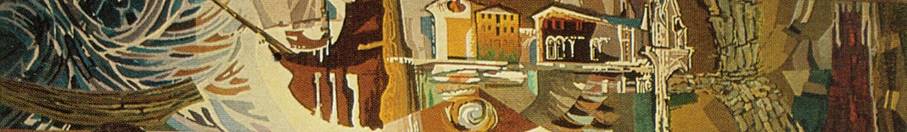

![]()

|

|

|

Depicting “certain landmarks in the Bloomsbury area”

this tapestry greets the Bank’s customers at London’s Tottenham Court Road

Branch. Celebrated designer, Sax Shaw

is commissioned to make this remarkable piece, and we believe that this

artwork is yet to be found somewhere in the World. The exterior of Martins’ Branch at

Tottenham Court Road is designed by Robin and Christopher Ironside, the

latter being responsible for the design of the original 10p piece used at

Decimalisation in 1971. Their design

includes Martins’ Coat of Arms in grained green granite above the door, and

for the Bank’s name to be carved into the marbled plinth above the windows:

![]()

Image © Barclays Ref 30/2958

![]()

The opening of Boston Branch in

1966 sees the creation of another tapestry, this time with a design that is

not quite so straightforward as the London Landmarks depicted at Totenham

Court Road. Indeed this time, representing the journey of the Pilgrim Fathers

from Boston to America, the tapestry is illuminated at night for passers-by to enjoy – having previously only used

drawings and paintings to sell the Bank, Martins is now taking advantage of

the time a Branch is closed, in order to raise in it the interest of

the public. Further examples are shown

below, commencing with this view of the Boston tapestry:

![]()

1966 – The Journey of the Pilgrim Fathers,

Boston, Lincolnshire

![]()

Martins’ Coat of Arms is

represented in towns across the country, and in many of them, the original

design is still to be seen, even if the owner of the building is no longer a

bank. Here are some from the vast selection,

followed by examples that you can still take a trip to visit – if you want

to…

![]()

|

|

Left – Ellesmere Port Right – Lancaster Above – Hedge End Below – Worcester St John’s

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

We must not forget the

decorations that were commissioned to appear along the front of Branch

counters. To the left, we have both

a Welsh dragon and Martins’ Coat of Arms at Bangor, and to the right, is

Stephenson’s Rocket which is commemorated at Stockton on Tees Branch.

Below - and like all counter

decorations, still missing – the four elaborate carvings from Newbury

Branch, depicting four local “activities”, Brewing, Chasing Farming and

Weaving… |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

![]()

All aboard, for the “Bug

‘n’ Duck” tour…

![]()

![]()

![]()

|

Image © Barclays Ref 30/1588 |

Image © Dave Baldwin December 2013 |

Image (Inset) © 1963 Barclays Ref 30/3092 |

On the corner of Vicar Lane and

Eastgate in Leeds (left and centre), you will still find Martins’ original

welcome above the door. Meanwhile at Watford 36 High Street (right) the

carving of the Bank’s coat of arms is still clearly visible after more than

fifty years. Remarkably well preserved on the wall of the Bank’s

Branch at Heaton Chapel (below), is this elaborate working of the Coat of Arms, with an

agricultural slant…

![]()

Main Image © Barclays Ref 30/1588 and Inset ©

2000 Michael Alderson

![]()

Last but not least, this lovely

almost art deco take on the Coat of Arms above the door at the Branch at

Claughton Village, Birkenhead which, sadly, closed in July 2013.

![]()

|

Image © Barclays Ref 0030-0196 |

Image © Martins Bank Archive Collections –

Robert Montgomery |

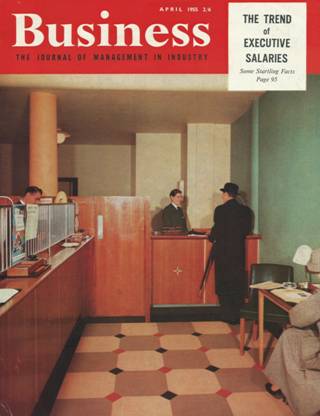

We still have not reached the true “shock of the new”,

that this page boasts, but believe me, get there we shall, and shocking it will

be. The 1960s sees an explosion of

art and media, that brings colour into the lives of a country that is still

confined to black and white television, and limited expensive colour in

magazines. Newspapers are still

completely monochrome, save for a few words such as “Late Edition” printed in

red ink in the top corner of the front page.

Any artistic expression is embraced as new and exciting, although

within a few years we will be easily able to sort out the rubbish from the good

stuff. Before we assault your eyes with some truly shocking examples of new BUILDINGS,

here are some artworks that you will no longer be able to find on the high

street…

![]()

Pushing the boundaries…

![]()

![]()

|

|

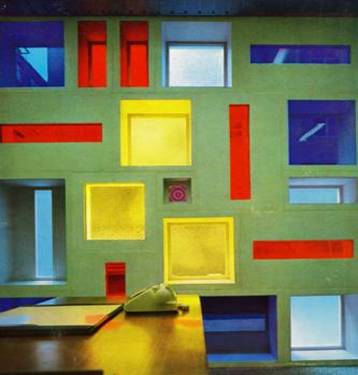

London too, has its share of

fine art: On the left Martins Bank’s Grasshopper and Liver Bird are

fashioned out of steel by Jan Kepinsky at the new branch at 84 Piccadilly

in 1964. Above, the horses represent

the T’ang Dynasty – something we are not sure quite conveys the fact that

you are inside the Branch at 25 Soho Square. Below (left), Westminster Branch makes

the headlines as “one of the most modern banks in Britain” in 1954, and

below (right) Ernö Goldfinger designs a VERY unusal window at Wigmore Street in 1968…

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

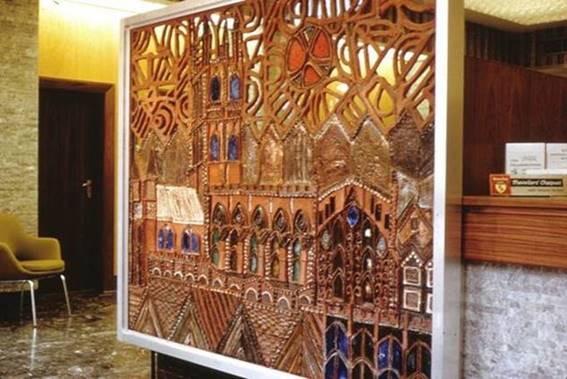

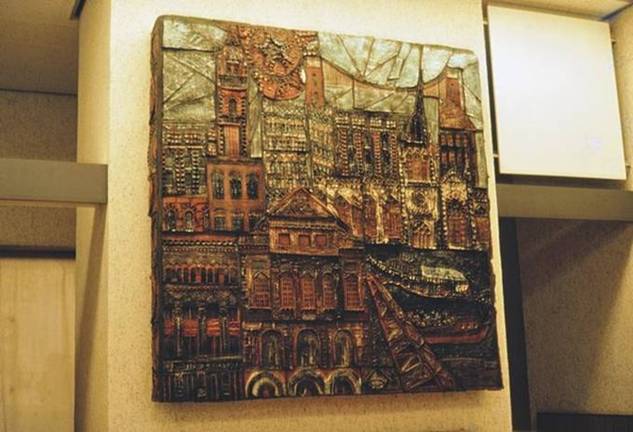

Meanwhile, in Martins Bank’s newest and fastest

growing district – South Western – a young ceramic artist is, to great

effect, given free reign over three branches… We have

already seen good examples of the Bank commissioning pieces of art work that

reflect the local area. Three such

works are created by Philippa Threlfall for the branches at Bristol Clifton, Cheltenham

High Street, and Gloucester. Philippa’s appeal for

information about the fate of her ceramic masterpieces is already featured on

our MOST

WANTED page, but we wanted to do justice to her work on

this page with large images.

![]()

![]()

BRISTOL CLIFTON, WHITELADIES ROAD

The design depicts various buildings

and landmarks in

Bristol

![]()

|

CHELTENHAM, HIGH STREET This unusual take on the Martins

grasshopper logo arrives just before the merger with

Barclays |

GLOUCESTER, 8-10 SOUTHGATE STREET Gloucester Cathedral, viewable from both sides:

shatter-proof glass prevented hands from penetrating the fretted ceramic.

Images

© Philippa

Threlfall 1966 to date www.philippathrelfall.com |

![]()

![]()

|

|

|

|

BOURNEMOUTH SCULPTOR PAUL FLETCHER’S CREATION “EXUDES

LOCALITY AND SECURITY” AT THE DOORS OF THE BRANCH. |

MARYLEBONE ROAD LONDON ANOTHER IMPRESSION OF STRENGTH AND SECURITY IS GIVEN BY THESE GATES |

The Shock of the New…

![]()

At last – our roll call of the

hideous is about to begin. These are

Branches of Martins that are either built as new, or to replace an older

office of the bank. In each case, the

best of intentions we are sure, were meant by those reponsible. It is only now that we can say – just WHAT

were they thinking?

![]()

Image © Barclays Ref 33/547

![]()

Welcome to dystopia 1967 – or

Thornaby on Tees Branch, as it is known – an office drowned in its own grey

drabness, a real nightmare in concrete.

How many people were subject to trudging those awkward walkways with a

pram, we can only guess. The next

crime occurs in Bexley, Kent, just before the 1969 merger – unfortunately, we

can’t even blame Barclays, as the whole thing is planned and executed by

Martins. Marvel for yourself, at what

takes the place of Bexley’s original branch…

![]()

|

|

|

In the face of such horror, will we ever be able to

sleep easy in our beds again? Well, NO

- here is another Kentish candidate, the lovely old branch at Welling is also

destroyed and replaced.

|

|

|

|

Images

© Barclays |

|

The North of the country is not immune either. We will concede that Hartlepool York Road

had to be replaced, the original North Eastern Banking Company building is

definitely past its sell by date - but the change is positively startling –

Mum, where’s my attic bedroom gone?

![]()

![]()

|

|

|

|

Images

© Barclays |

|

|

|

|

Where in the universe have we

landed? Is this one of the wobbly sets from the 1960s episodes of “Dr

Who”? Even worse - no need for L S D when paying in your £ S D

at the new Watford Branch. The uneven

cobbled effect on the floor, clashing with walls that look as if they might

close in on you at any minute, must have made for an “interesting” visit to

Watford…

![]()

Image ©

Barclays

Things could have been a lot worse…

![]()

Our Designing Martins feature ends with a short look

at Martins’ obsession with mock tudor.

As if advertisments giving an impression that Martins Bank goes back

to Roman times aren’t enough, they do also have a habit of sticking faux

wooden beams across the front on some of the Branch buildings, to give them

that “ye olde” feel. Here are some of

the suspects:

![]()

|

There is

of course, nothing wrong with a traditional looking Tudor or mock

Tudor building, and we would sooner have a hundred in this style, as

opposed to the some of the miserable offerings Martins ends up with by the

time of the merger. Two branches

that are both now closed, will never lose their attraction as perhaps the

finest examples of the traditional, and these are at Lymm, (below

Left, and Chester, (below, right)… |

At

Stratford upon Avon (left) and Prestatyn (above,

right) there is the distinct suggestion of a conveyor belt, churning out

identically themed branches. Nantwich (below

right ) is even more fanciful, and at Swansea (below left) we even have several floors in the Tudor Style.

Image © Martins Bank Archive

Collections |

|

|

|

|

Image (Re-touched) ©

Martins Bank Archive Collections |

Image © Martins Bank Archive Collections - J C Wens |

We hope you have enjoyed this

tour around some of the designs, artworks and buildings that make Martins so

distinctive. Please use our search

facility and/or A to Z to visit the individual offices concerned, to learn

more about each of the individual branches mentioned.

![]()

![]() M

M

![]()